Threat Hunting: Clearing Up Misconceptions

Before diving into what threat hunting is, let’s first clarify what it is not. It is not the same as cyber threat intelligence (CTI) or incident response (IR), though it is closely connected to both. CTI can serve as a strong foundation for a hunt, while IR often follows a successful hunt to address identified threats.

Threat hunting is also not about simply deploying detection tools—though it can enhance their effectiveness. It is not limited to searching for Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) within an environment; rather, it focuses on uncovering threats that have evaded detection systems powered by IoCs.

Additionally, threat hunting is not the same as continuous monitoring, nor does it involve running arbitrary queries on monitoring tools. Most importantly, it is not an exclusive task reserved for a select group of experts. While expertise is valuable, threat hunting is a discipline that can be learned and practiced by a wider range of professionals.

Type Of Threat Hunting (TH):

- Un-Structured approach Hunts :

- Data Driven TH: Hunting by Data observation; A practical starting point for threat hunting is generating hypotheses based on data observations. Simply put, you determine what to hunt for by analysing the data already available to you.Technically work with the data you know you have.

- Structured approach Hunts:

- Intel-Driven Hunts : Hunts that triggered by Intel tip or trend of exploitation.

- Entity Driven : Hunting and investigating around specific entity (either suspected to be affected or high value entity commonly termed in some cases as Crown Jewels) which are holding uch as crucial intellectual property and network resources.

- TTP Driven Hunts : Hunting (looking ) for specific Tactics , tools or methods of breach (attack chains) commonly known as procedures a specific threat actor utilises.

To effectively disrupt an attacker’s success, we must go beyond static indicators like domains, IPs, and hashes. Instead, it’s crucial to understand the tools attackers use, their timing, and their methods. Where does their activity begin? What are their objectives? How do they achieve them? These insights serve as valuable starting points for threat hunting, offering context that is better suited for human analysis rather than purely automated detection. - Hybrid: Blending approaches.

Data Driven Approach : (Un-Structured Approach)

- Defining the Research Goal : A solid research goal can be set on following parameters :

- When conducting a data-driven hunt, it’s essential to both understand the available data and align it with adversary activity. Roberto Rodriguez highlights key questions that help define a clear research objective.

- What specific threat are we hunting for?

- Do we fully understand our data? Do we have a structured data repository?

- Is the relevant data collected and stored in our environment?

- Have we mapped logs to known adversary behaviors?

- How specific should our approach be?

- How many techniques or sub-techniques can a single hypothesis cover?

- Are we focusing on the technical enablers or the broader behavioral patterns?

- Model the Data – Centralize logs in a data lake and structure them with data dictionaries.

- Emulate the Adversary – Simulate attacker behavior using mapped techniques. MITRE ATT&CK provides structured guidance. Mordor (GitHub) offers pre-recorded security event simulations.

- Define & Validate Detection – Establish a detection strategy based on structured data, test in a lab, and refine as needed. HELK (GitHub) supports advanced analytics.

- Document & Communicate – Maintain thorough documentation (jupyter notebooks) throughout the hunt to ensure clarity and actionable insights.

TaHiTI – Targeted Hunting Integrating Threat Intelligence : (Structured Approach)

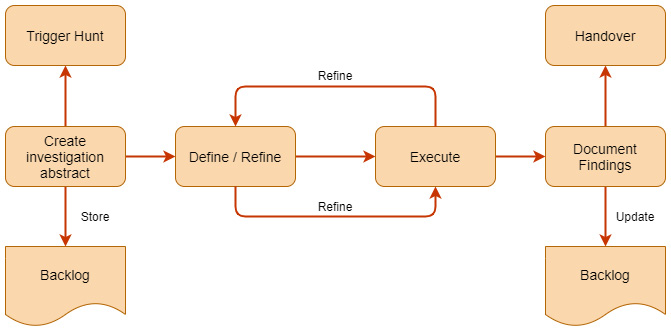

TaHiTI emphasizes structured threat hunting by utilizing intelligence on adversaries’ tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) to guide investigations. The methodology helps security teams contextualize findings and refine their approach to detecting advanced threats. It follows an eight-step process, which is categorized into three key phases.

The TaHiTI methodology distinguishes between five major trigger categories:

- Threat intelligence

- Other hunting investigations

- Security monitoring

- Security Incident Response: With data gathered from both historical incidents and red teaming exercises.

- Other: Examples include finding out what the Crown Jewels are and how they could be compromised, studying the MITRE ATT&CK™ Framework, or just the hunter’s expertise.

Phases of TaHiTI

- Initiate Phase – The trigger for a hunt is analyzed and translated into an investigation plan. Triggers can originate from five sources: threat intelligence, prior hunts, security monitoring, incident response, or other security inputs. The formulated plan is then stored in the backlog for execution.

- Invoke the hunt

- Create an abstract about what hunting for

- Threat Intel Based : selecting IoCs which are well-contextualised, ensuring hunts are driven by relevant, actionable intelligence rather than static indicators.

- Situational : This is also known as the Crown Jewels Analysis.

- Domain Expertise : Based on Threat Hunter expertise.

- Store in Journal (or say Backlog)

- Investigate Phase (Refining) – Security teams analyze relevant data, searching for indicators of compromise (IoCs) and adversary behaviors that may have bypassed existing defenses. This phase involves hypothesis-driven exploration based on threat intelligence and past hunting experiences.

- Define (come back after below)

- Enrich Investiagtion Abstract

- Determine The Hypothesis

- Define the Data sources

- Decide on Analysis techniques

- Execute :

- Retireve the Data

- Filter the data

- Analyse the data ; check whether it correlates with Hypothesis

- Validate Hypotheisi and identify what is missing and add it again )

- Go back to Define stage

- Define (come back after below)

- Operationalize Phase – Findings from the investigation are applied to enhance security operations. This includes refining detection rules, updating security controls, and enriching threat intelligence with newly discovered TTPs and IoCs.

- Handover and update the progress in Journal

- Document the findings

- Update Journal(backlog) Decide The next steps

Source : Tahiti Overview

TaHiTI distinguishes between five processes that may be triggered as a result of the threat hunting investigations:

- Security Incident Response: Initiates an IR process.

- Security monitoring: Creates or updates use cases.

- Threat Intelligence: Uncovers a new threat actor’s TTPs.

- Vulnerability management: Resolution of discovered vulnerabilities.

- Recommendations for other teams: Recommendations are issued to other teams in order to improve the overall organization security posture.

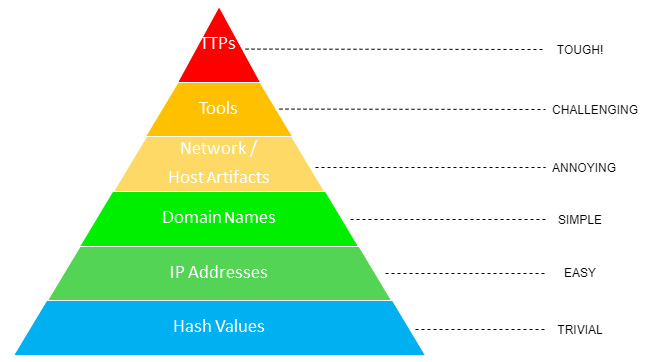

Selecting Right IoC for Hunt:

The Pyramid of Pain, created by David Bianco, illustrates the effectiveness of different types of Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) in disrupting adversaries. At the base are hash values, IP addresses, and domain names, which are easy for attackers to change, making them less effective for long-term threat hunting. As we move up the pyramid, network and host artifacts, tools, and TTPs (Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures) become harder for adversaries to modify, increasing their value for detection and response.

For effective threat hunting, focusing on TTPs and behavioral patterns rather than static indicators ensures a proactive defense, forcing adversaries to alter their methods significantly—causing them real pain and making attacks more costly and difficult to execu

One response to “Threat Hunting : Core”

[…] To continue Go to : Practical Threat Hunting approach […]

LikeLike